《育甘塔短片輯》映後協作組織小教室

場次:10/15(日)12:20

主持人:女性影展策展人 陳慧穎

講者:導演 蒂帕.譚拉

文字整理:林琳、陳慧穎

攝影:蔡菁芳

*此記錄將以章節式文章的型態整理,本篇照片皆源自育甘塔電影集社官方網站 Source of the Photos:https://yugantar.film/。

1960、1970年代的政治社會動亂

育甘塔電影集社在1980年代創立,但想先補充一下之前的社會背景。自六〇、七〇年代以來,印度經歷了政治跟社會上的動亂,全國上下有非常多的抗爭運動、社會運動,牽涉當時的物價、失業、土地遭到上層階級非法奪取等問題。我們有一個關於育甘塔電影集社的網站(https://yugantar.film/),上面有很多的文宣資料供參考。

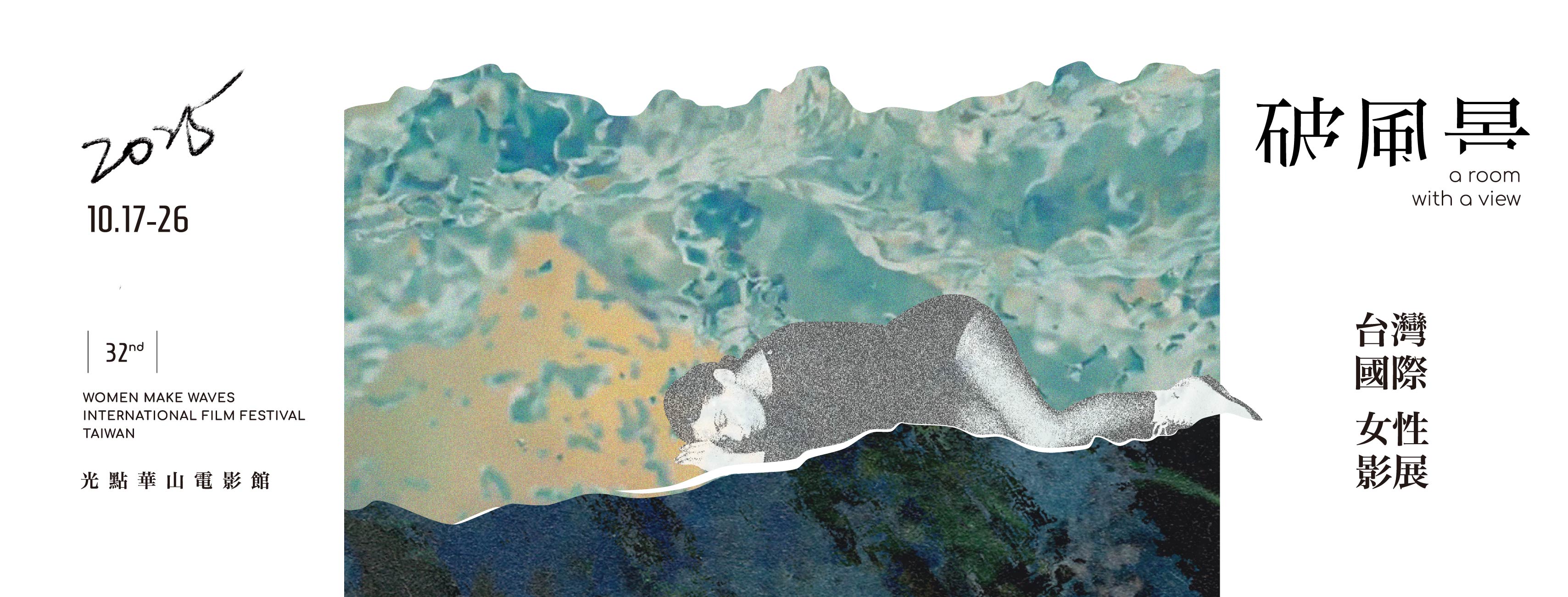

這個標語非常有名:「誰擁有土地?那些在土地上耕作的人」,這個標語的背景事實上是一場由女性農民帶領,對抗佛寺的土地抗爭。

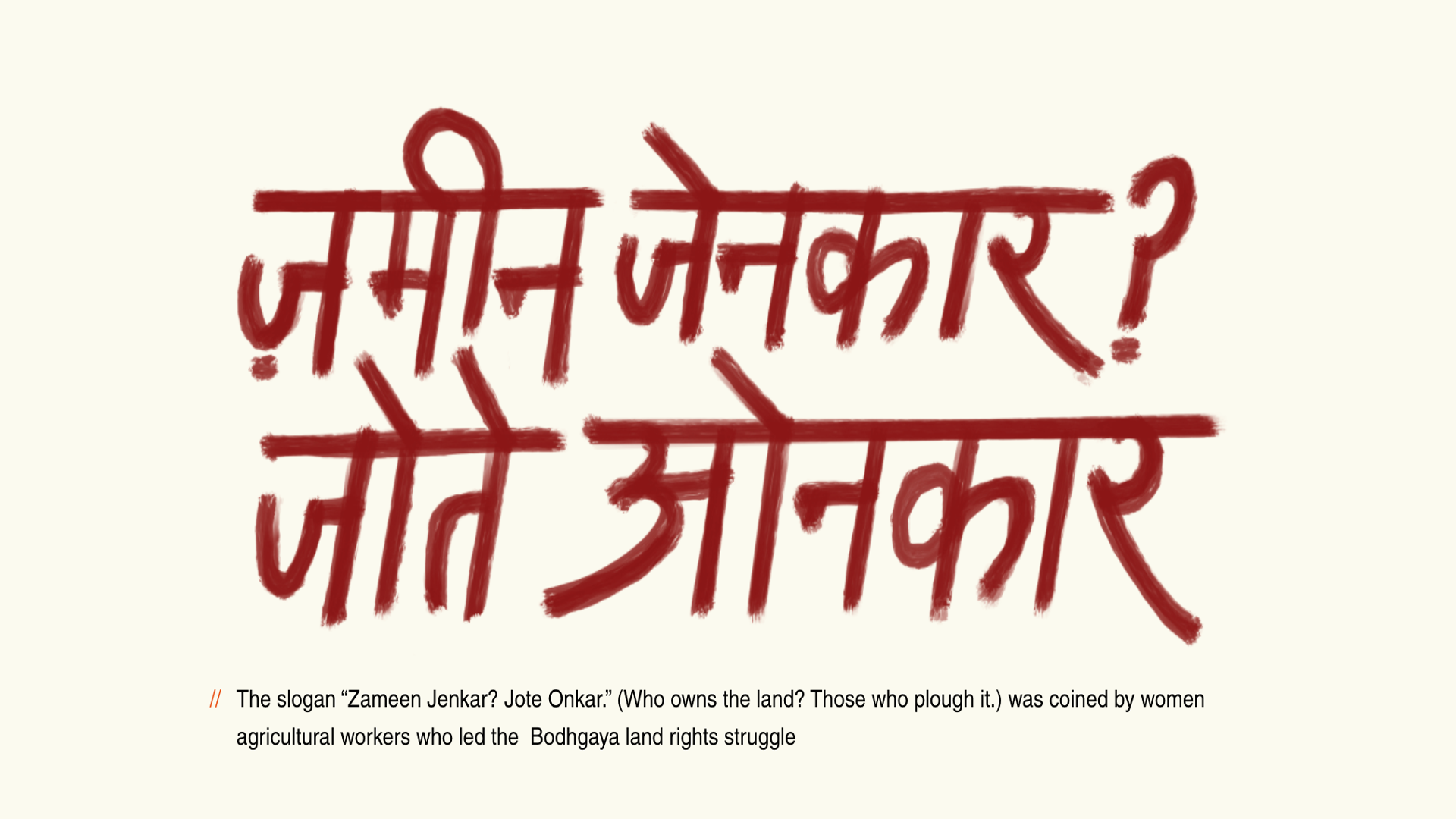

這一張則是印度最早出現的女性主義學生組織「Progressive Organisation of Women」,她們非常的活躍,她們發表的宣言(https://reurl.cc/v06KWa) 非常有意思,很令人驚豔的宣言。她們也用泰盧固語寫成的標語:「我們不是奴隸,我們不是女神,我們就是人」。我必須說那是一個很令人興奮的時代,這些則是當時的女性主義雜誌的封面。有些帶有左翼色彩,有些則沒有。

政治分水嶺:緊急狀態時期

直到1975年代,我們已經看到有非常多的學生不惜放棄課業,投身於這些運動當中。當時有一個很重要的政治分水嶺,甘地夫人宣佈緊急狀態時期(1975-1977),所有的新聞媒體都被審查,非常多的異議者都被關進監牢,其中包含很多的學生,很多人被關、遭到虐待、消失或是被殺害。

緊急令時期結束後,開始有了選舉,許多年輕人、學生被釋放出來,引起很大的社會能量。當時也有非常多年輕女性都動員起來,投身社會運動。那是一個充滿創意、極具能量的時代。她們抗議非常多事情,包含強暴事件,尤其是在警局的強暴事件,這引起了非常大的示威。

在後緊急令時期,看到了很多自主性的女性運動,開始成立一些社團跟組織,所謂的自主,我指的是它不屬於任何政黨或是沒有得到任何組織資助。也就是說,當緊急令解除,也就迎來自主性女性運動蓬勃發展的時期。

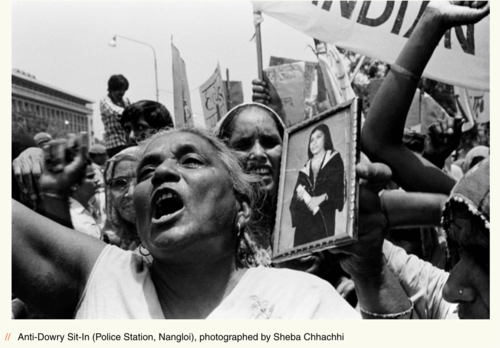

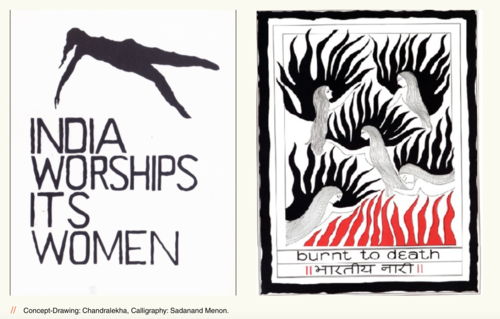

這張照片是攸關於一個很嚴重的問題:嫁妝死亡,因嫁妝問題造成的年輕女性死亡事件。在這個抗爭當中,你可以看到一位母親拿著她遭殺害的女兒照片。我會給大家看這些照片的原因是,在八〇年代,基本上女性是一直在街頭抗爭的,全國上下四處可見各種抗爭在發生。這裡則是一些非常經典的海報,這些都是女性主義政治參與的珍貴歷史文獻。

育甘塔電影集社經驗

那個時代對我來說深具啟發性,當時我跟我的朋友們就想說「我們為何不開始創立一個女性電影集社呢?」我們當時的規定很簡單:既然我們看到了這些女性勞工的社會動員,是否能將之視為一種政治性行動的動員形式?我們是否能把我們拍的這些影片到不同的女性勞動組織、團體或社群中放映,藉此開啟一系列的對話,或許讓她們看完片之後,也想要創立自己的社群,或是讓對話在既有的組織裡發生。

自1980年到1986年,我們的影片在印度非常多地方放映,去社區活動中心、工會辦公室、大學教室、甚至是街上。電影很常被拿去放映,那時我們帶著非常重的器材,包括放映器材、膠卷、音響,我們都自己帶,公車不讓我們把這些器材帶上去,我們就綁在公車車頂上,現在大家都是用數位影像,很難想像那個情境。但對我們來說這些放映非常重要,因為我們能夠得知不同背景的女性怎麼看待這些電影,以及我們可以怎樣更好去談論或理解當下正在發生的事情。

來談一下我們製作的方式,這點很重要。我們希望能以一種「共同著作」(co-authoring)的方式進行,而不是「合作」。我們的電影集社也跟其他女性組織、協作組織一起工作,我們是一起共同創作。

這個過程很有意思,部分原因歸因於我們的定位。我們是女性運動的參與者、倡議者,同時我們拍電影。要為電影找到觀眾其實是很容易的,因爲我們跟全國上下的女性組織、團體都有聯繫,合作起來很容易。創作過程是,最一開始,我們通常會跟這些女性組織長時間的工作,討論很多問題,包括我們會希望這些影片說一些什麼?哪些是值得討論的重要議題?有什麼議題是你也感興趣的?那概念比較是「並肩作戰」,而非「為誰而說」。

舉例來說,《菸草燎原》這部片,裡面有個大規模罷工,晚上集體睡在地上的畫面。這一場罷工真實發生的時候我們不在現場,我們整個錯過了。但這些菸廠女工很堅持罷工場景一定要重演。你可以想像嗎?有三、四千女性參與,你要怎麼進行?我們完全沒有信心可以重現,但這些女工直接說:「交給我們」,她們會負責組織、安排好一切,包括食物等等。還有,當時沒有任何一間工廠老闆願意讓我們拍攝,直到有女工終於找到一間工廠願意給我們拍,但只能拍三小時。因為我們從來沒有進去拍過,所以一進到工廠裡面,都是靠著女工在指揮大局,可以說是女工們自己執導了那一個場景。她們會說,「你得拍這一、二、三、四」。另外,除了拍攝的內容之外,旁白也是一樣的情況,我們有劇本,會請她們講一些旁白,但可能有四、五十個女人在場,就說「這不對,那不對,要換種講法、換個語言」等等,她們是緊密參與整個製作過程的。還有初剪,我們都會放這些初剪給她們看,然後她們會有一些修改的意見。

關於劇情短片《純屬虛構?》,我們跟著一個女性組織「Stree Shakti Sanghatana」合作,成員不是工人階級,比較是中產階級,我們坐下來討論了非常多問題,關於家庭暴力、關於婚姻。這就是我們劇本的開始,透過一系列的激烈討論及切身經驗的分享,一同把這寫成劇本,我們的故事想要討論的是心裡層面的暴力,可能在婚姻中女性孤單、被忽略,另外也想討論女性情誼。片中你可以看到有女性同事間的情誼,且這個女性情誼是具有激進的潛力的。在1982年,我認為能以這樣的型態共作,便是一種很激進的概念。

大概在五年之後,這些片不再能放映,因為原始膠卷損壞,對於一個電影創作者來說,電影無法再被放映是一件很痛苦的事。直到有一次,一位德國的研究學者Nicole Wolf來到印度研究印度的紀錄片,我們相約見面,我用口頭跟她介紹電影,但我沒辦法放映這些作品給她看。直到後來,因緣際會德國柏林的兵工廠(Arsenal)有機會修復這些片,我們才得以看到今天的修復版本。

影片被修復之後,到非常多的電影節去放映,我很好奇在影展的人們是以什麼樣的角度去看,因為這些作品在製作的當時,並沒有想到影展的面向,也還沒有這樣的概念。這些影片好像變成女性的歷史、電影歷史中的一部分。我覺得要怎樣再去介紹這些影片是非常有趣的議題,尤其在印度,你要怎麼重新介紹這些影片?這對我們來說是一個很重要的問題。

目前我們會舉辦一些特別的放映,邀請一些女性家事工作者、曾經遭受過家庭暴力的女性、在菸草工廠上班過的女性,讓她們坐在觀眾席裡面,在最後QA時間請她們發表自己的想法,分享當時的情況跟現在的情況有什麼不一樣,這樣能用很有機的方式談論歷史。而事實證明,現在女性的處境並沒有太大的改善。

QA

Q1:三部紀錄片的人社會階級是什麼?是否也能談談語言?《純屬虛構?》劇情很像2021年上映的一部電影《偉大的印度廚房》,不知道導演有沒有看過,想問導演的看法,這樣是不是代表40年來印度女性的處境並沒有太大的改善?

A1:對於印度觀眾來說他們能夠透過語言去分辨角色所屬的種姓階級,比方說像工會的那兩部片,很多都是種姓階層底層的女性,另外可以分辨階層的是抗爭的訴求,很多都是關於尊嚴與自尊,因為那是種姓階層底層女性就連最基本的尊嚴和自尊都沒有。

關於《偉大的印度廚房》,這部片大概是幾年前拍攝的,《純屬虛構?》則是1980年代拍攝的,的確有人提到這兩部片具有相似之處。我覺得家庭觀念與女性在婚姻裡的地位改變並沒有很多,改變的是女性現在是要外出工作,她們可以離開家裡,得到一些高薪的工作貼補家用,但她們在家庭決策的地位依然很低。

或許當代女性會渴望更多改變,但家庭的觀念依舊是強烈影響印度社會的一股力量,你只要去看一個例子:跨階級、跨宗教的婚姻在印度是會遭受嚴厲的懲罰與批評的,也就是說家庭的概念仍非常鞏固。

Q1 《純屬虛構?》的女主角是否是女性組織的參與者嗎?是否也能談談結尾有些突兀的結束。

Q2 針對突兀的結尾,我不知道該怎麼回答,但我覺得重點是結束在女性之間的情誼。你說的沒錯,這部片的主角來自女性組織的成員,事實上裡面所有的演員都是女性組織的成員。這部片其實是我們最受歡迎的影片,每次放映都會受到滿大的迴響。大家會很自然地分享自身的經驗,也可能歸因於我們在寫劇本的時候,把大家日常經歷的憤怒、不滿都寫進去,那些情緒是能與其他女性產生共鳴的。

Social and Political Background

We have a website: https://yugantar.film/ where you can see documents, images and photos, all kinds of things. This collective was started in 1980. And to give you a bit of the political and social context of what was happening, if you look at the sixties and seventies, there were a lot of protest movements in many parts of the country. There was a lot of social unrest related to the rise in food prices, urban unemployment, industrial unrest in relation to wages. And there are a lot of movements related to land, particularly land that had been illegally seized by what we call upper-class landers. This slogan was a very popular one: "who owns the land? Those who plough it." This slogan was actually coined by women agricultural workers who led a huge land struggle against Buddhist monastery.

This photograph is one of the first feminist students groups, Progressive Organisation of Women. They were really active and their manifesto(https://reurl.cc/v06KWa) is very interesting to read. A a very impressive manifesto. And this was one of their main slogans in Telugu, "we are not slaves, we are not goddesses, we are human." I also want to say that it was a very exciting time, and these are some feminist magazine covers, with all kinds of organizations. Some were more left oriented, some were not.

Watershed Moments: Declaration of Emergency

By the time we get to 1975, you find that there are a lot of students who have abandoned their studies to join the protest movements. And there was a very important watershed moment when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared an emergency from 1975 to 1977.

During that time, most of the opposition had been imprisoned and press were censored. A lot of young students who were political active were also imprisoned. Some of them were tortured, while many of them were disappeared or basically killed. Now what happens is, entering the post-emergency period, once elections are declared and young people were released, there was a huge uprising. In fact, it was a very creative and energizing time that you have a lot of young women who are part of the movement, who are active in many struggles. For example, talking about rape, custodial rape mainly, which occurs in police station. That became a huge campaign where a lot of women got mobilized.

In post-emergency period, you see a lot of what is now autonomous women's groups and feminist organizations. By “autonomous”, I mean they were not part of political parties, nor did they get institutional funds. So once emergency was lifted, here comes the birth of the autonomous women's movement. This photo connects to a very big issue: dowry murder or the killing of young women for dowry. Here in the protest, you see the mother was carrying the picture of her daughter who was killed. I thought I should show you these because it felt like in the 80s, women were on the streets all the time, all over the country in so many protests. And here are some of very classic posters that are all part of our feminist political history.

The Yugantar Experience

It's that time for me and friends, who decided, “why don't we start this collective?” The objective was fairly simple: there were movements of working class women, whether it was domestic workers, tobacco workers. Can we look at these as forms of political mobilizations? Can we circulate these films to other groups of other women workers, construction workers for example, and hope to start some kind of conversation wherever they want to either create some kind of political organization or let the conversation happen inside the organization. Basically it is a very modest kind of loop, so to speak.

From 1980 to 1986, Yugantar films were circulated very widely, very often these screenings happening in community center, sometimes on the street, in union offices, in college classrooms, wherever we could find actually electronic connection. These films were screened so often. You have to imagine there were 16 mm prints, with the projector and the sound box to go physically to these places to screen the films. And often they wouldn't let us to put them in the busses, so we put them on the top of the busses. The screening was very important to us because with each screening, what we were learning is really what women understood from the film and how we could then speak better to what was happening.

To share something about the filmmaking process, we really wanted to make it co-authored process. This is not a collaboration that our collective was working with women's groups and their collective. And we were co-authoring with them.

This process was very interesting also because of our position. We were part of the women's movement, and we were also activists in the movement. So actually getting audiences for the films was very easy for us because we were in touch with most of the women groups across the country. What we did is, initially, we had to spend a lot of time with the collectives. In the sense of, what do you want this film to say? What do you want it to be about? What are the issues that you think are important for women like yourself to listen to? It was more an act of "standing with", not "speaking for".

For example, in "Tobacco Embers", you see the big strike with thousands of women on the street. At night they're sleeping there. This is something that we had missed. We weren't there when the strike happened. And they were very keen to have this strike be re-enacted. Can you imagine, with 3 or 4 thousand women, how do you do this? We didn't feel confident and they said, "just leave it to us. We will organize it. We will organize the food, we will organize everything." Also, when there was no factory owner willing to give permission to film inside the factory, finally they managed to get one factory owner to agree. And he gave us 3 hours. Once we got in, it was the women workers who directed the entire shoot. They said, you have to film this. 1, 2, 3, 4, This is what you have to do. So even to that extent, what we were filming, when we have narration, there would be a group of at least 40, 50 women who would say, "no, that's not right. Change the language. No, this is not correct." So as much as we could involve them in the production of the film, including the rough cut, we would always screen the rough cut and get feedback as to what they want to change.

For "Is This Just a Story," we worked with a feminist activist collective that was not working class, more of middle class. We came up with the idea of how do we talk about domestic violence? And that script emerged from very intense conversation in the group where we all shared, for example, our life experiences growing up as girls, what happens in marriage? And that script arose in that fashion. And we really wanted to speak about two things. One is the more kind of psychological violence. And at the same time, we also wanted to talk about female friendship. And I think the film has that combination where you have two women who are work colleagues, and the female friendship also has a kind of radical potential. At that time. I think in 1982, this was a very radical idea that we could work in this way.

After about five years, the film prints were in no condition to be screened. They were completely destroyed. And in a sense, it's very hard for the filmmaker when your films disappeared. Researcher Nicole Wolf, who was crucial to the restoration of these films, as you can see them today, had come to India to do research on Indian documentary. And when we met, I told her about the film, but I couldn't show the film. And there was a point where finally Arsenal in Berlin were able to make these films available after such a long time. And it's always curious to me that they're being circulated now in festivals, because at that time, when we made the films, that was not an intention. We had no such concept. So now I'm always curious whether they're seen in some part of feminist history or cinematic history. The thing is, how do you reintroduce, particularly in India? This is a big question for us, so that it really has a function.

What we did in India is that we had special screening, but we didn't have a typical QA like this. What we did is in each instance, we had women, domestic workers. We had women who victims of domestic violence. We had tobacco workers and women. And they would watch the films with the audiences at the same time. And then they would respond in terms of what has changed or what remained the same. And I think doing it that way taught history together very organically and easily. And in fact, practically not much has changed.